9 Mac Optimizer Software to Tune Up Your Mac

We all love macOS for its performance. However, here're apps you can get it even better and much smoother than…

Apple Silicon didn’t just make Macs faster. It quietly rewrote how Macs deal with heat.

We moved from Intel-era laptops that doubled as space heaters to machines that stay cool, silent, and composed under workloads that once sent fans screaming. For most users, thermals stopped being something you noticed.

But that doesn’t mean cooling stopped mattering.

With Apple Silicon now spanning from M1 all the way to the latest M5 Macs — and macOS 26 Tahoe doubling down on silence and efficiency — the cooling story has shifted from “can it stay alive?” to “can it stay consistent?”

This is the real story of how Apple Silicon changed Mac cooling — and where the limits still live.

Intel Macs were designed around bursts of performance followed by aggressive cooling. High wattage meant high heat, which meant loud fans and frequent throttling.

Apple Silicon flipped the equation.

M-series chips deliver dramatically higher performance per watt, allowing macOS to sustain workloads at far lower power levels. Tasks that once demanded 35–45W on Intel Macs often run in the 15–20W range on modern Apple Silicon.

The result isn’t peak speed — it’s predictability.

Instead of sprinting and collapsing, Apple Silicon prefers a steady cruising speed. Long exports, compiles, or renders often complete at a consistent pace without the mid-task slowdowns Intel users grew used to.

Cooling didn’t disappear — it became less dramatic.

Part of Apple Silicon’s thermal calm comes from architecture, not fans.

Modern M-series chips use a hybrid design:

This means your Mac isn’t constantly lighting up high-power cores just to stay responsive. Less wasted energy means less heat — especially during everyday work.

For most users, this is why fans rarely turn on at all.

Apple didn’t just redesign the chips — it rewrote the rules for fan behavior.

On Apple Silicon Macs, macOS is deliberately conservative about spinning fans. The system prioritizes:

Fans are often held at low speeds until internal temperatures climb quite high — sometimes well above what experienced users expect.

From Apple’s perspective, this makes sense:

For 90–95% of users, this approach works beautifully.

But it creates a new reality for power users.

Apple Silicon Macs almost never fail thermally.

What users experience instead is performance throttling.

Under sustained workloads — video rendering, compiling large projects, local AI inference, or gaming — heat accumulates over time. macOS responds by subtly reducing clock speeds to stay within its preferred thermal envelope.

The key point:

This is a policy decision, not a hardware limitation.

The chip isn’t overheating. macOS is choosing quieter operation over maximum sustained throughput.

This is why many professional users notice:

Cooling didn’t become irrelevant — it became strategic.

On Intel Macs, fan control was relatively straightforward.

On Apple Silicon, it’s a different story.

Apple has increasingly locked down low-level hardware controls. With the M4 generation, fan behavior changed in ways that broke older control techniques entirely. Tools that worked on M1–M3 simply stopped having any effect.

Supporting manual fan control on modern Apple Silicon requires:

The situation stabilized with M4, and M5 continues using the same fan control approach — but temperature monitoring has become far more complex. On some M5 Macs, thousands of internal sensor points must be mapped and interpreted just to present meaningful data.

The result:

Manual control is possible — but it’s far more fragile and nuanced than it was in the Intel era.

By default, macOS is reactive.

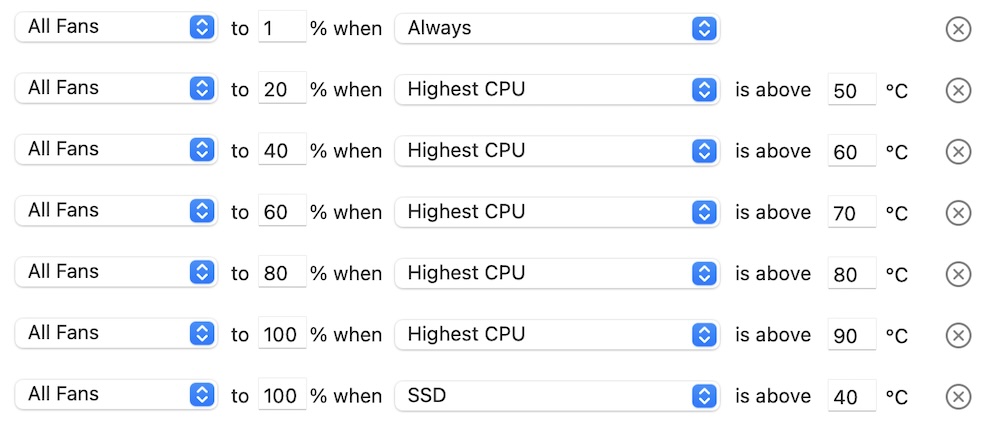

It allows temperatures to rise first, then responds — gently at first, aggressively only when necessary. Third-party tools like TG Pro can adjust fan behavior, but in most cases they operate after macOS has already decided cooling is needed.

This is enough for many users.

But professionals often prefer a different trade-off:

Pre-cooling a system before a long render or compile can keep it out of aggressive throttling territory entirely.

Apple optimizes for silence.

Power users often optimize for predictability.

Both choices are valid — but only one is exposed by default.

macOS now includes user-facing Power Modes that directly influence thermal behavior.

Low Power Mode, for example:

These modes don’t replace manual control, but they show Apple’s intent:

cooling is now part of system policy, not just hardware response.

Apple wants thermals to feel invisible — even if that means leaving some performance on the table.

Apple Silicon is efficient, not magical.

Under long, heavy workloads:

Once a system becomes heat-soaked, macOS will gradually pull back performance to protect internal components and battery longevity.

This is normal behavior — and unavoidable physics.

This is also why developers like Matt Austin spend days mapping thousands of undocumented M5 sensors—just to give users visibility into what’s actually happening.

Apple Silicon didn’t eliminate the need for cooling.

It eliminated the drama around it.

For most users, Apple’s approach delivers exactly what they want:

For power users, the story is more nuanced:

The real shift isn’t technical — it’s philosophical.

Apple optimized for calm.

Professionals sometimes want control.

And knowing when — and why — that trade-off matters is the difference between a Mac that feels fast and one that stays fast when the work gets heavy.

Cooling didn’t disappear.

It just stopped shouting.

We all love macOS for its performance. However, here're apps you can get it even better and much smoother than…

Here we’ll walk you through the essentials and some great 3rd-party apps — to tune up your MacBook beyond its…

MacPaw launches Moonlock to strengthen cyber security for CleanMyMac X.